The Mysterious Call of Tibet: VERTU IRONFLIP Takes You to the Big Picture of Your Heart

In the ancient and mysterious land of Tibet, where the sacredness and serenity of nature can be felt with every

Jackson Pollock’s “No.1,” enamel and metal paint on canvas, 161.6 x 261.6 cm, 1948.

Throughout the long history of art, each era has seen talents leading the way, thus forming the various schools of thought we see today. When it comes to schools of thought, most people can easily name their representative figures and stylistic characteristics. However, what exactly is the first work of each school? And how should we determine the so-called “first”? Today, let’s explore the “first piece” in some of these schools of thought.

A. Henry Fuseli’s “The Nightmare”

B. Eugène Delacroix’s “The Massacre at Chios”

Delacroix is undoubtedly one of the representative artists of Romanticism, and his work “The Massacre at Chios” is also the first time the term “Romanticism” was used to describe a visual artist. However, before this, traces of Romanticism had already appeared in many paintings.

Eugène Delacroix (Eugène Delacroix) “The Massacre at Chios” (The Massacre at Chios), oil on canvas, 345×419cm, 1824.

In contrast, the name Henry Fuseli can be considered a niche. His work “The Nightmare” depicts a woman in a nightmare, with a monkey sitting on her and a dark horse faintly appearing in the background. There is no exact time for the end of Neoclassicism and the birth of Romanticism, and Fuseli’s paintings reflect how the two genres walked side by side in the early days.

Henry Fuseli’s “The Nightmare,” oil on canvas, 101.6 x 127 cm, 1781.

A. Honore Daumier’s “Rue Transnonain, le 15 Avril”

B. Gustave Courbet’s “The Burial at Ornans”

“Beauty lies in truth, not in fantasy,” and depicting reality in a truthful manner is the creed of realism. Before the rise of realism as a movement in the 1840s, Daumier’s caricatures were already expressing social injustice. In April 1834, government troops brutally massacred some residents, and in opposition to the monarchy, Daumier revealed the event through a print.

Honoré Daumier (Honoré Daumier) “Rue Transnonain, le 15 Avril”, lithograph, 28.6×44.1cm, 1834.

Daumier undoubtedly revealed a strong sense of realism in his works, but as a cartoonist, he was excluded from the “art circle” at that time.

Courbet, who claimed to be the “standard-bearer of realism,” depicted an ordinary ceremony in his work “The Funeral at Ornans” with a huge scale, causing a strong reaction from critics and the public. He was quite confident, calling “The Funeral at Ornans” the funeral of romanticism. After being rejected by the World Exposition in 1855, the artist held a solo exhibition “On Realism” near the exhibition and wrote a “Realism Manifesto,” establishing his “first position”.

Gustave Courbet, “A Burial At Ornans,” oil on canvas, 315x664cm, 1849-1850.

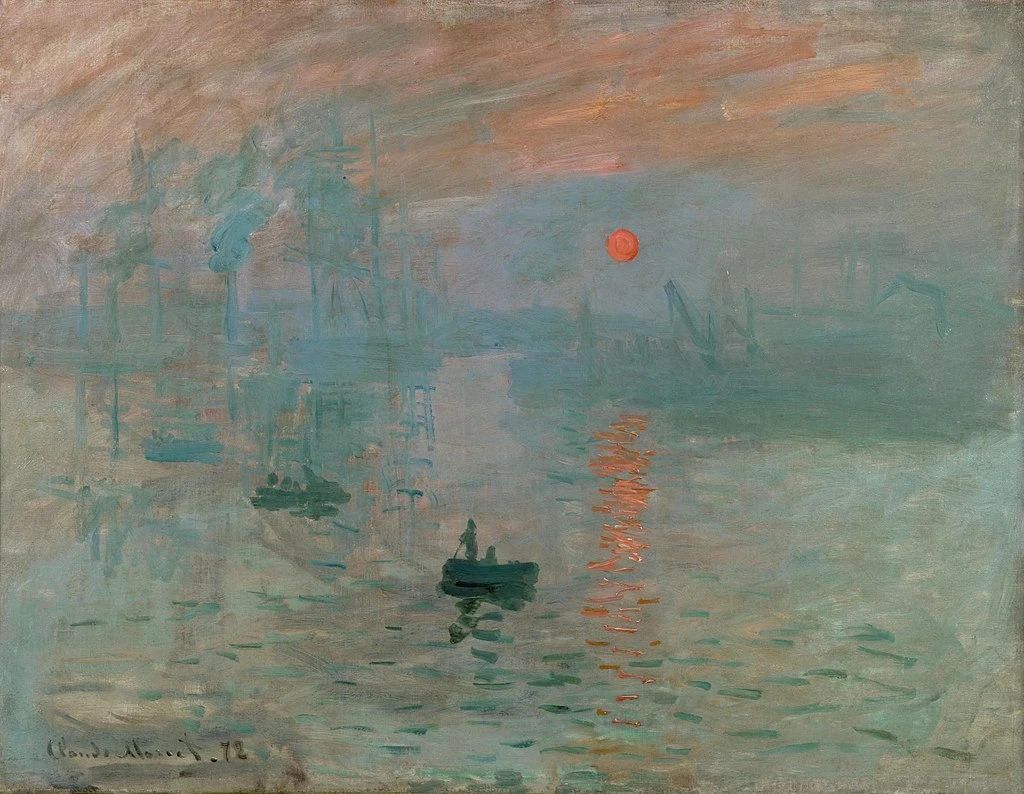

A. Monet’s “Impression, Sunrise”

B. Manet’s “Luncheon on the Grass”

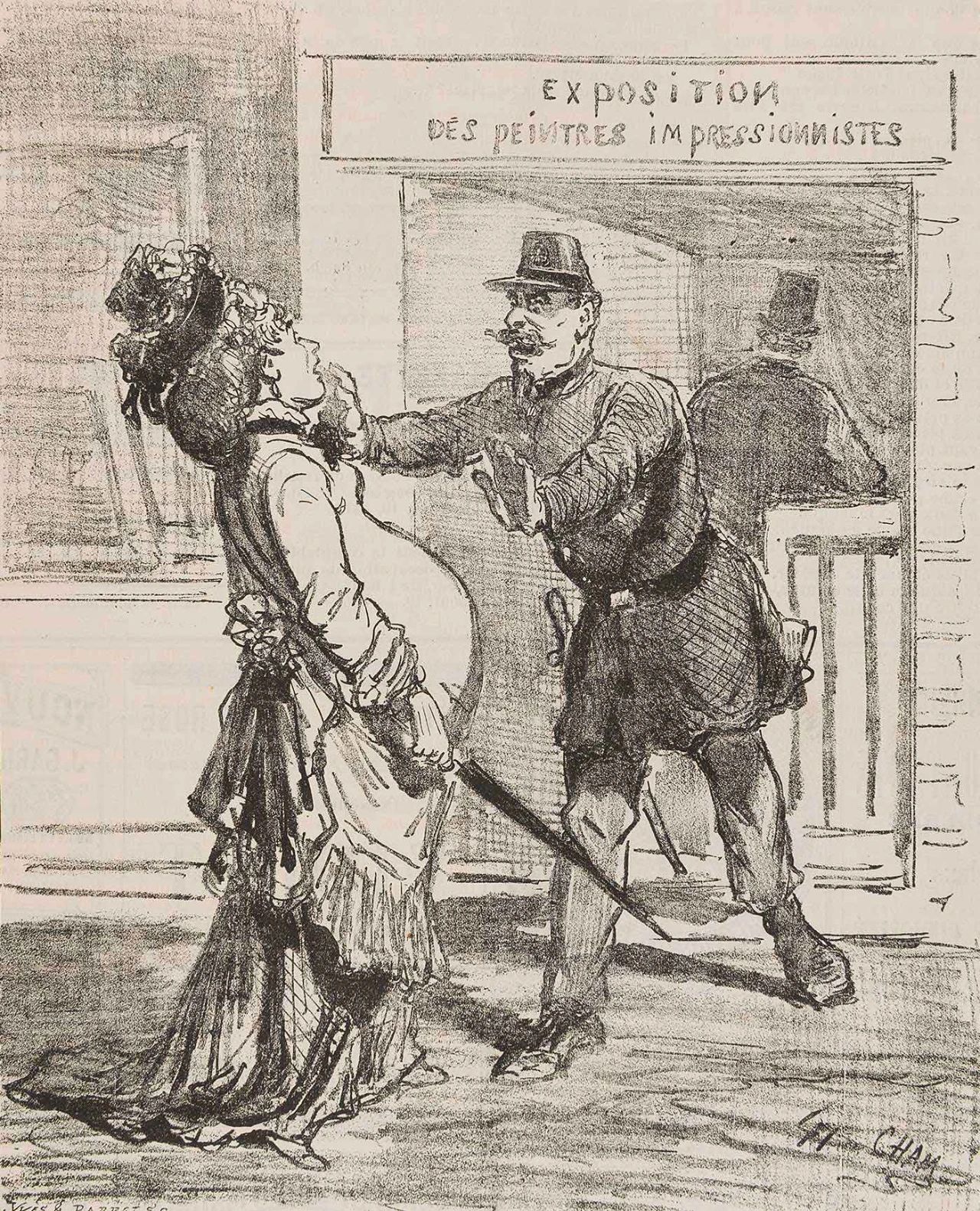

Many readers must have heard of the notorious event in 1874 – a group of independent artists held an exhibition outside the official salon. Critic Louis Leroy’s satire on the exhibition piece “Impression, Sunrise” gave rise to the term “Impressionism,” and the work has since become the seminal piece of the movement.

Claude Monet (Claude Monet) “Impression, Sunrise” (Impression, Sunrise), oil on canvas, 48×63cm, 1872.

*An illustration from the 1877 Parisian magazine “Le Charvari,” depicting a pregnant woman being stopped by a guard as she attempts to enter an Impressionist exhibition.

In fact, the term “impression” had previously been used to describe Manet’s work. Although Manet never collaborated with Impressionist artists in exhibitions (as he still hoped for official salon recognition), this group regarded him as the leader of the revolutionary spirit – his disdain for traditional nude subjects and deviation from form and technique in “Luncheon on the Grass” inspired Impressionist artists. Monet’s 1865 work “Luncheon on the Grass” is an example of his response to Manet.

Édouard Manet’s “Luncheon on the Grass” (Le déjeuner sur l’herbe), oil on canvas, 207×265cm, 1863.

Claude Monet, “Luncheon on the Grass,” oil on canvas, 418×150cm, 1865

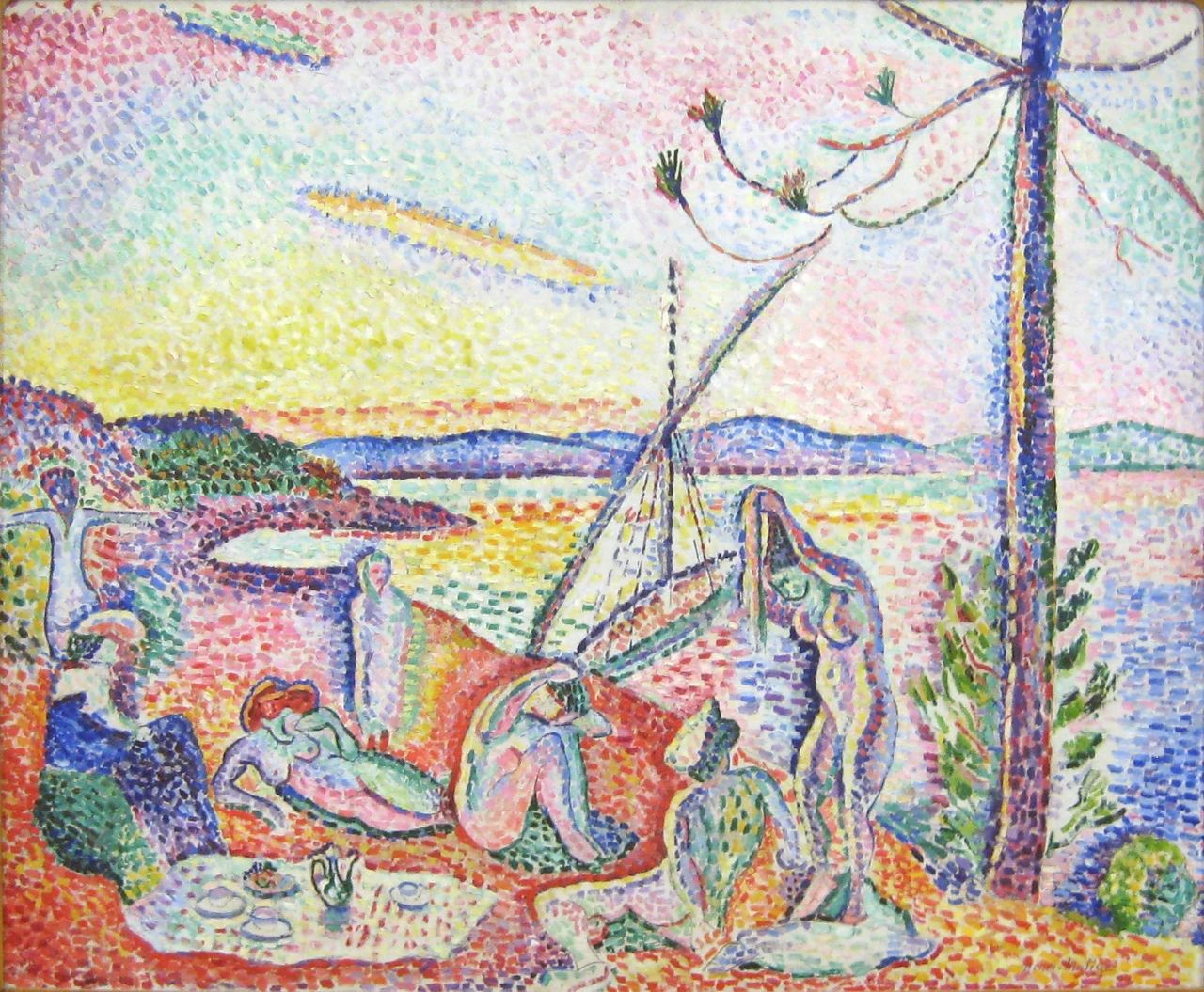

Henri Matisse’s “Luxe, Calme et Volupte” is an oil painting on canvas, measuring 98.5 x 118.5 cm, created in 1904.

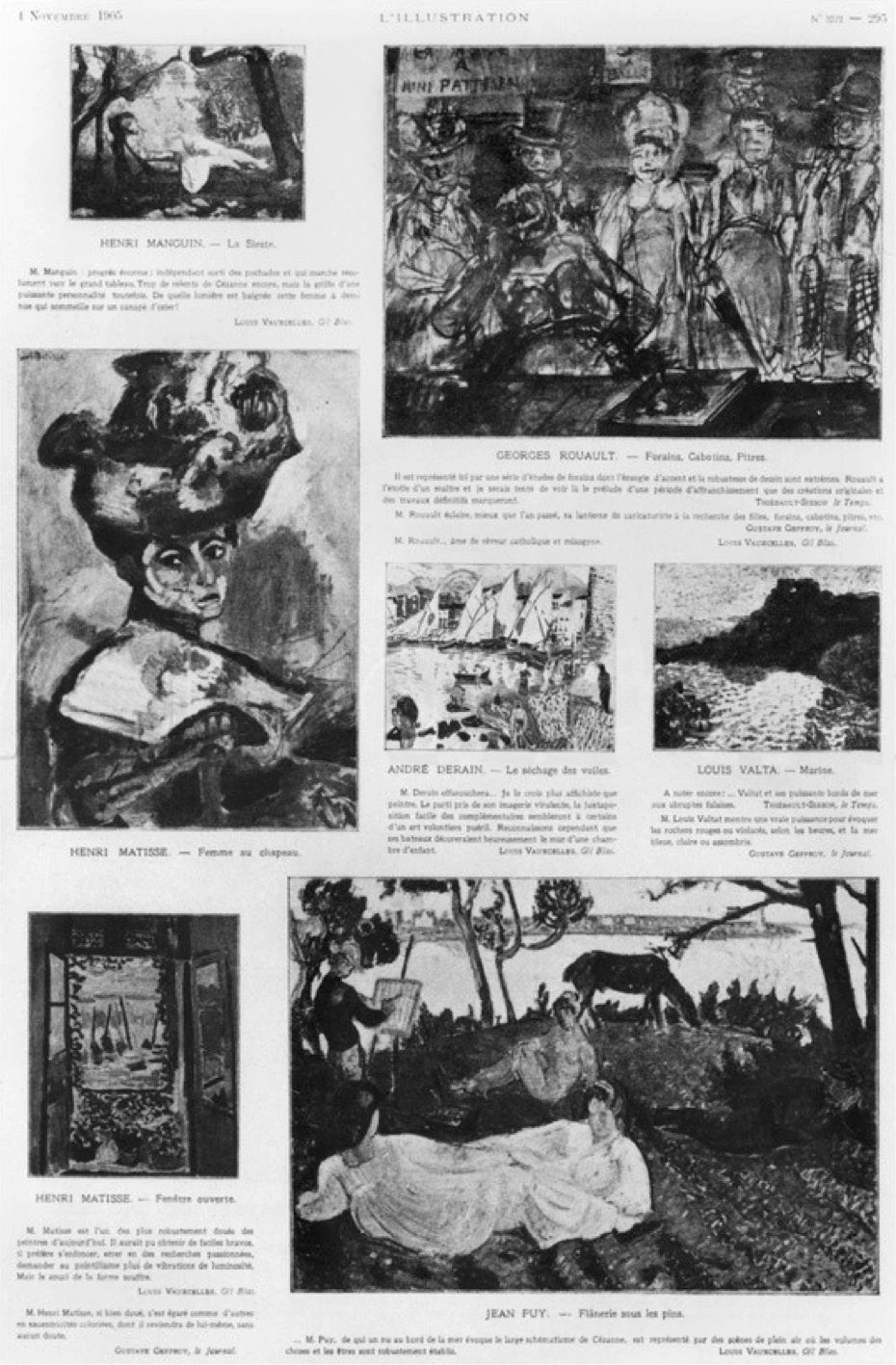

The stylistic characteristics of Fauvism are first reflected in Matisse’s 1904 painting “Luxe, Calme et Volupte”. The following year, Fauvist paintings were officially exhibited in Paris, shocking the visitors of the annual Autumn Salon. Critic Louis Vauxcelles referred to the works as “wild beasts” (Fauves) due to their “indulgent pure colors” – hence the name of the movement.

“Beast Fauvist” Autumn Salon Clippings in 1905

It is worth mentioning that Matisse’s inspiration is deeply related to his teacher, Gustave Moreau. Moreau was a professor at the Paris Academy of Fine Arts and it was he who taught the expressiveness of color. Matisse once said, “With him, I was able to find the most suitable work for myself.”

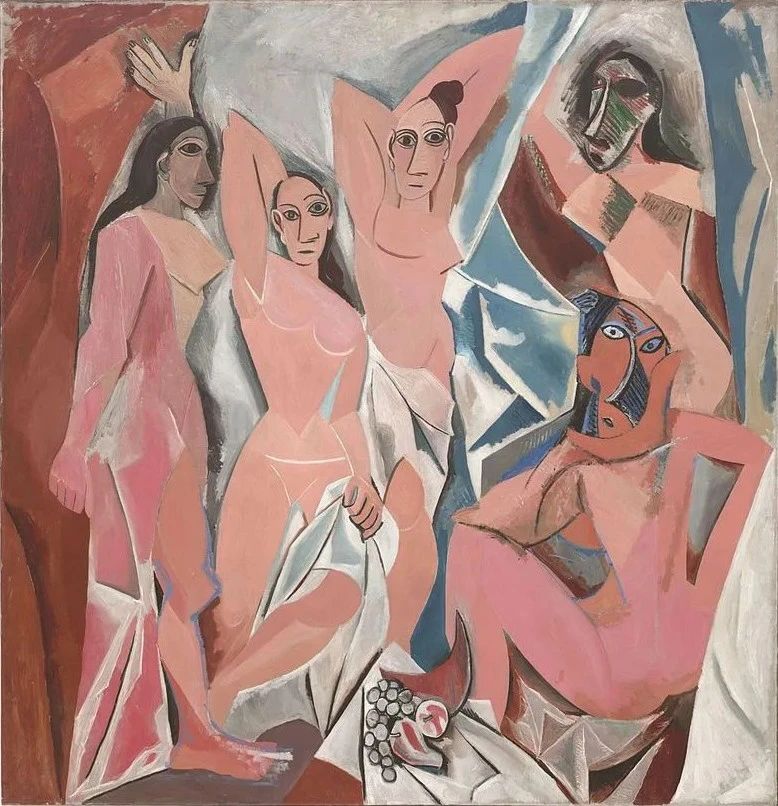

A. Picasso’s “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon”

B. Georges Braque’s “Houses at l’Estaque”

Most art historians recognize Picasso’s “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon,” created in 1907, as the seminal work of Cubism. The images of the five women were inspired by various sources – the influence of African tribal art, the borrowing and competition from Matisse’s “The Joy of Life,” Cézanne’s treatment of space and volume, Picasso’s talent, and Georges Braque’s analytical experiments…

Pablo Picasso (Pablo Picasso) “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon” (Les Demoiselles d’Avignon), oil on canvas, 243.9×233.7cm, 1907.

Nowadays, Picasso is still as popular as ever, while Braque’s name is relatively dim. In fact, the term “cube” was first used to evaluate Braque’s work (the critic was Louis Vauxcelles, who made fun of “wild beasts”), which gave birth to the term “cubism”. Braque’s “Houses at l’Estaque” is also often regarded as the first primitive cubist landscape painting.

Georges Braque, “Houses at l’Estaque,” oil on canvas, 40.5×32.5cm, 1908.

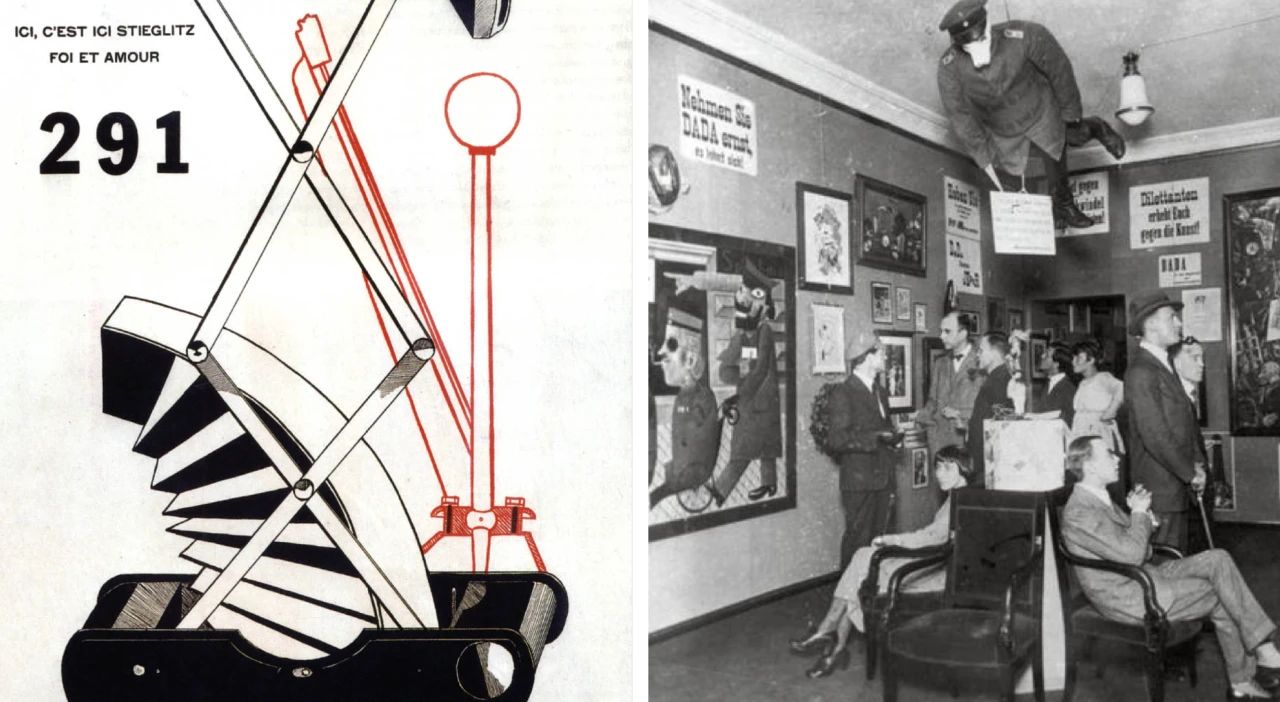

A. Francis Picabia’s “Ici, C’est Stieglitz”

B. Jean Arp’s Collage

In 1916, poet Hugo Ball founded the “Cabaret Voltaire” in Zurich and established “Dadaism,” with Jean Arp being one of the members of the cabaret. His abstract collage works were hung on the walls on the opening night. In an article, he also wrote: “I declare the word ‘dada’ to have been born at 6 o’clock in the evening on February 8, 1916.” With all these, he seems to be the well-deserved first.

“Voltaire Cafe,” 1916

However, between 1915 and 1916, Francis Picabia and Duchamp came to New York to escape the war and published works with Dadaist colors in the magazine “291,” even earlier than Arp. The term “Dada” had not yet been used to describe their works at that time, but later generations found that the spiritual core was surprisingly consistent. After the war, the founder of the “Dada” magazine only heard about “New York Dada.”

Francis Picabia, “Ici, C’est Stieglitz,” 1915

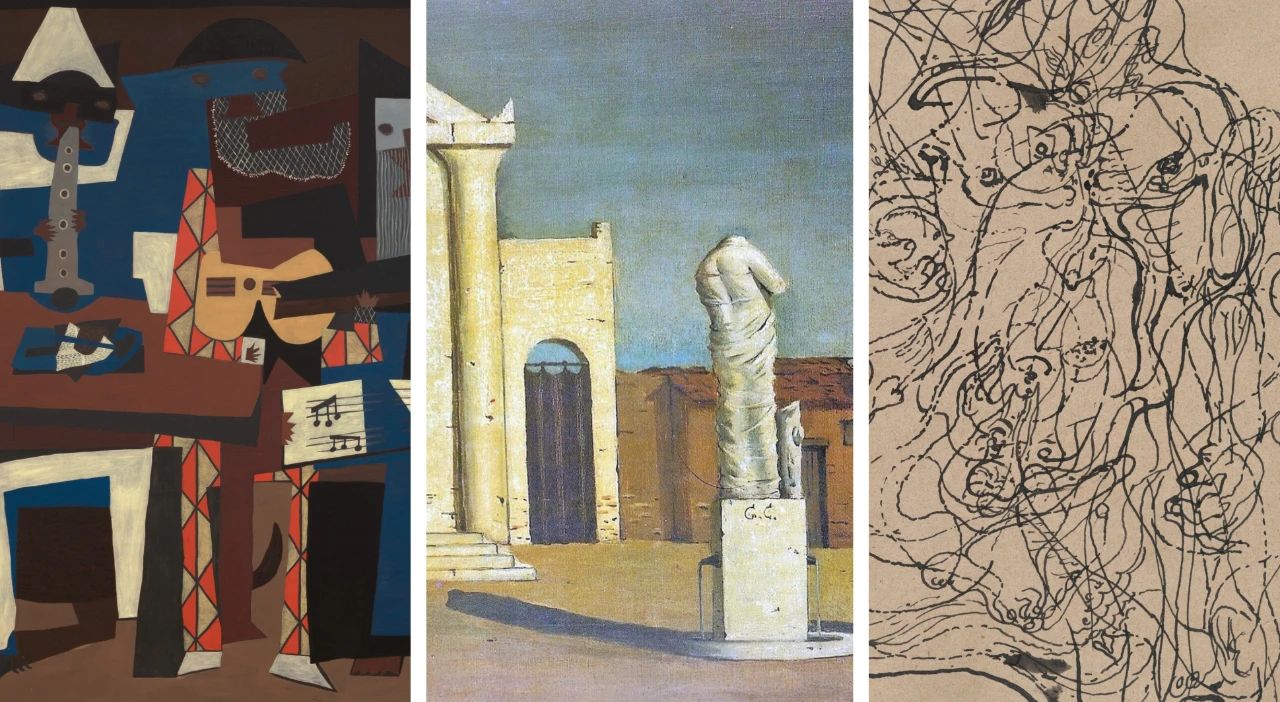

A. Picasso’s “Three Musicians”

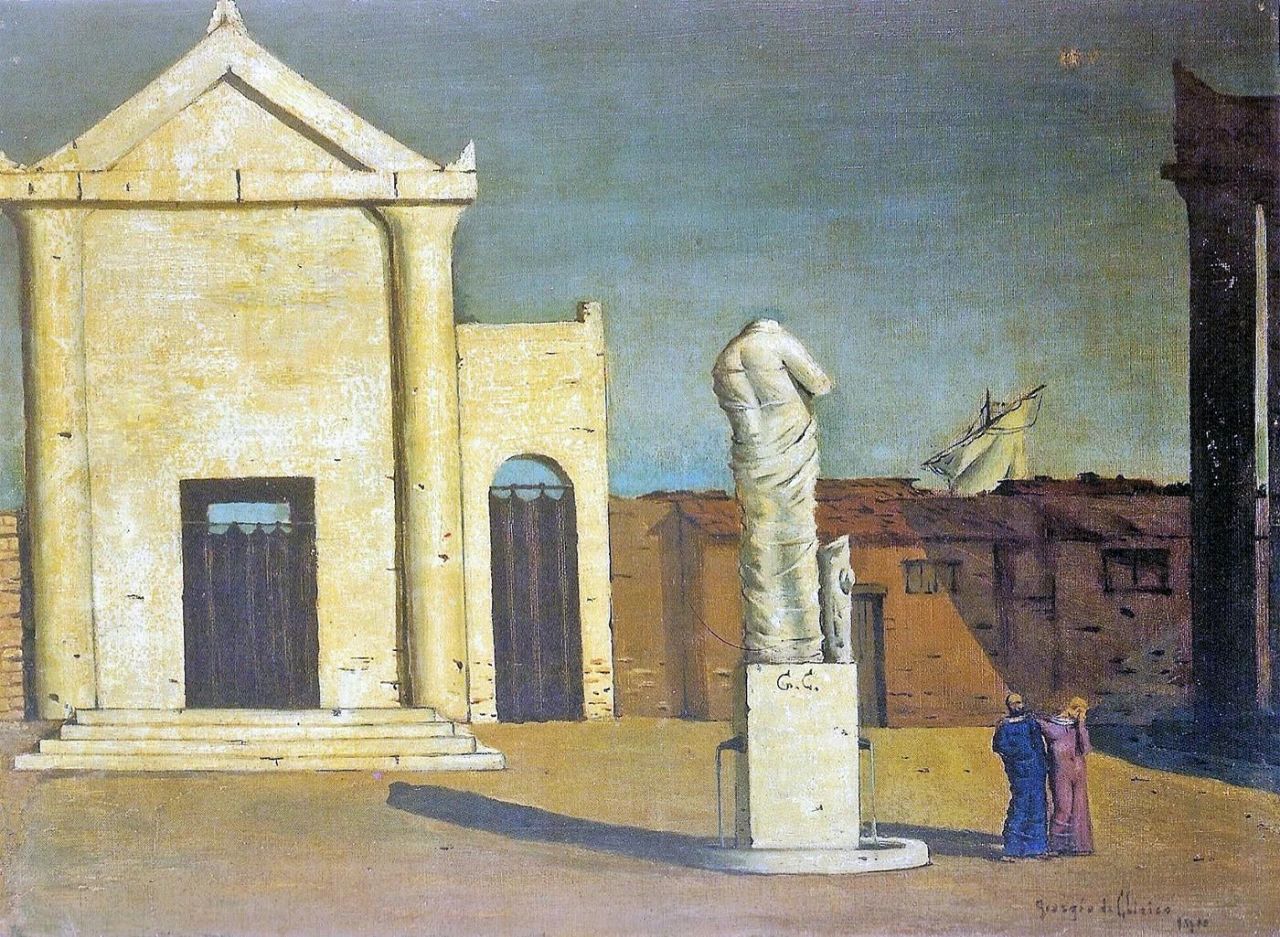

B. Giorgio de Chirico’s “The Enigma of the Afternoon”

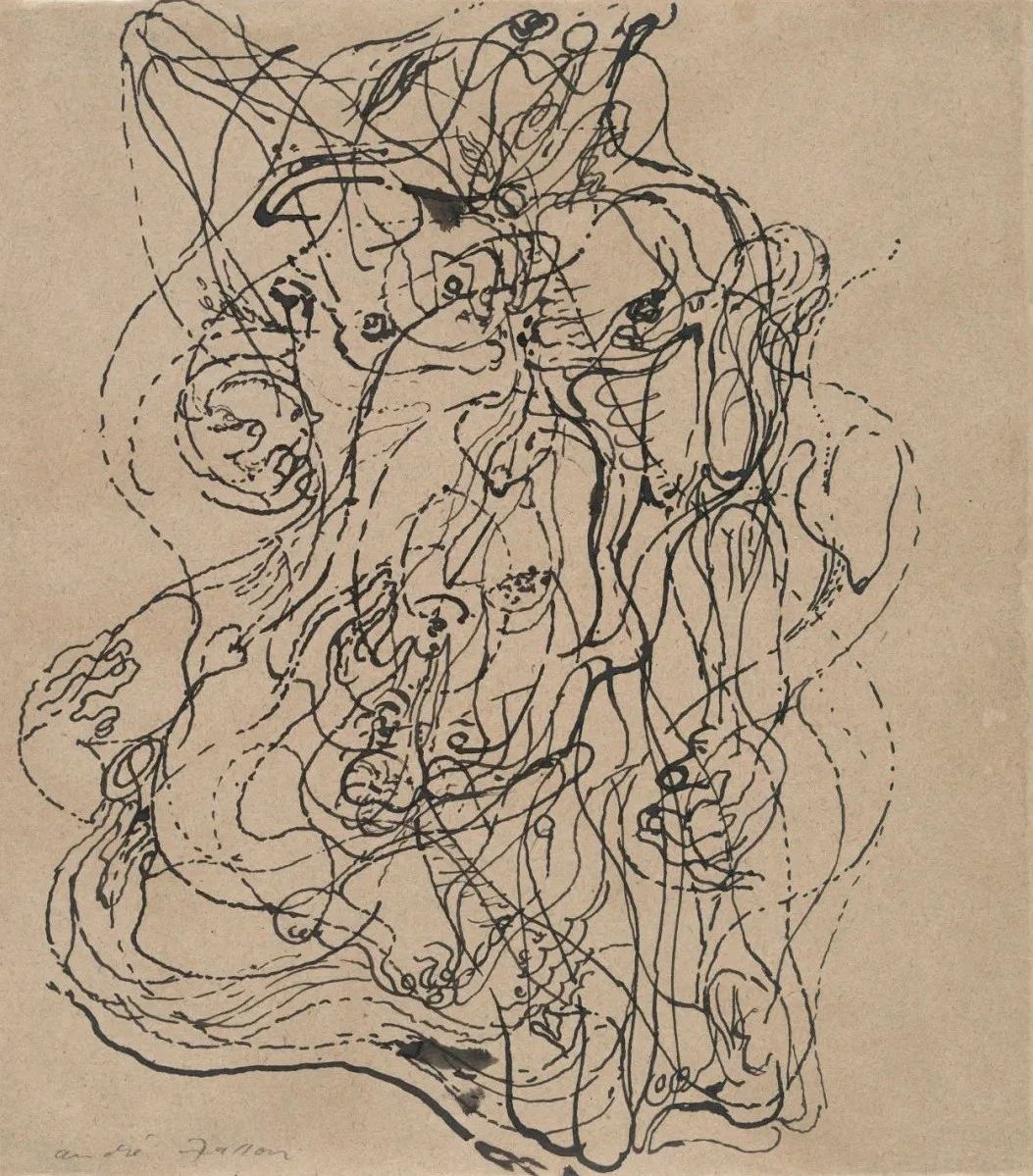

C. André Masson’s “Automatism”

Surrealism officially began with writer Andre Breton’s 1924 “Surrealist Manifesto,” which emphasized a new form of expression called “automatic writing,” aimed at unleashing the imagination of the subconscious. Initially, surrealist poets were reluctant to ally with visual artists, as they believed that the tedious processes of painting, drawing, and sculpting contradicted the spontaneity of free expression. However, the inspiration for the movement actually came from Giorgio de Chirico’s paintings.

Giorgio de Chirico’s “The Enigma of an Autumn Afternoon,” oil on canvas, 53×72cm, 1910.

After the movement began, artists competed to create. André Masson pioneered automatic drawing in 1924 – drawing lines in a trance-like state and then further imagining and drawing; Max Ernst followed the next year by inventing frottage.

André Masson’s “Automatic Drawing,” ink on paper, 23.5×20.6cm, 1924.

It may come as a surprise that Picasso is associated with surrealism – Breton saw Picasso’s cubism as the first step in liberating the artist’s imagination, and the dreamlike elements in his 1921 work “Three Musicians” coincide with surrealism. However, Picasso himself, although he participated in several surrealist exhibitions, did not consider himself a surrealist.

Pablo Picasso’s “Three Musicians” (Three Musicians), oil on canvas, 200.7×222.9cm, 1921.

A. Mark Rothko’s “No.3/No.13”

B. Jackson Pollock’s “Mural (1943)”

C. Arshile Gorky’s “The Liver is the Cock’s Comb”

Abstract Expressionism evolved from Surrealism, and this transformation was completed when the symbolic elements of Surrealism disappeared. The works of Armenian artist Arshile Gorky reflect the beginning of this transformation – with lines and colors cycling repeatedly, one can see the influence of artists such as Miro, Masson, and Kandinsky.

Arshile Gorky’s “The Liver is the Cock’s Comb,” oil on canvas, 1944.

Subsequently, Abstract Expressionism developed into two major categories: Action Painting, represented by Jackson Pollock, and Color Field Painting, represented by Mark Rothko. Pollock’s transformation occurred in 1943 with this mural, while Rothko formed his mature style in 1949.

Jackson Pollock’s “Mural (1943)”, oil on canvas, 243×604cm, 1943.

Mark Rothko’s “No.3/No.13”, oil on canvas, 216.5×164.8cm, 1949.

A. Eduardo Paolozzi’s “I Was a Rich Man’s Plaything”

B. Richard Hamilton’s “What is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing?”

It was not Andy Warhol or Roy Lichtenstein, but before these two artists emerged in the United States, Pop Art had already begun to develop in the United Kingdom in the 1950s.

Eduardo Paolozzi was a Scottish artist and an important member of the British post-war avant-garde art movement. His collage “I Was a Rich Man’s Plaything” is an important foundation of Pop Art, which includes elements of popular culture such as pulp fiction covers, Coca-Cola, and recruitment advertisements. In particular, the “POP” cloud emerging from the gun barrel makes this work the first to contain the word “Pop.”

Eduardo Paolozzi (Eduardo Paolozzi) “I Was a Rich Man’s Plaything”, paper collage, 35.9×23.8cm, 1947.

Hamilton’s collage is also often considered the first work of pop art. He used cutouts from magazine advertisements to create a family scene that both praises consumerism and criticizes the decadence of the American post-war economic boom. The lollipop in the man’s hand is inscribed with the word “POP,” which also accurately captures the essence. However, even to this day, when people think of pop art, they often do not think of these two artists.

Richard Hamilton’s “Just What Is It That Makes Today’s Homes So Different, So Appealing?” collage, 26×25cm, 1956.

After exploring the “firsts” of various genres, it is not difficult to find that the “first” is often hard to define. Looking vertically, the art movements of each era build upon each other and cannot be completely separated. Picasso and Matisse in the 20th century could also be influenced by primitive African sculpture. Looking horizontally, literature, music, painting, and other forms of art cannot be separated. Surrealism was originally a literary movement, but it was inspired by painting and then influenced visual art again.

In the long history of art, some people claim to be the first, some stand out, and more people are not remembered. A “first dispute” may allow us to see more stories behind familiar names.